LCNet -- Skin Cancer Classification

A lightweight lesion classification network

Unlike much other work in this space, the developed model is a singular, relatively lightweight Convolutional Neural Network. The model performs impressively, presenting both strong diagnostic capability and generalization across categories, advancing accurate and efficient deep learning algorithms for skin cancer detection.

Background

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are biologically inspired models that build on the work of the biologists Hubel and Wiesel. Hubel and Wiesel proposed an explanation for visual processing that built a layered architecture of neurons in the brain, involving 2 categories of cells – complex and simple. Simple cells are primary, and search for simple patterns, while tertiary complex cells combine earlier neural outputs with high-level inputs like spatial information to produce visual perception, even with shifts in the input signal like spatial change. CNNs build on this biological framework, applying the same ideas of local structure, layering, and spatial invariance to their architectures.

The most important layer of a CNN is the convolutional layer, which is responsible for extracting features from input signal. This is done using a filter, through a process called convolution. A filter is nothing more than a two-dimensional array of values (called weights) that is systematically passed over the whole of the input data. Convolution is the process by which high-level information is extracted from this data. With every change in position, the model calculates the dot product between the filter and the corresponding cells in the input data, creating a final output called a feature map. The feature map is a representation of the important characteristics of the image, and is used to determine the final output of the model. The key to using convolutional layers in deep learning is that the weights in a filter are adapted as information flows through the model, allowing the models to “learn” how to identify inputs. In the developed model, filters become adapted to identify characteristics of skin cancer like color, texture, and edge irregularity, and ultimately determine the diagnosis.

A limitation of convolutional layers is that they are very sensitive to the position of features within an input image, meaning that minor changes can have a significant effect on the model’s output. To compensate for this fact, pooling layers are implemented. A pooling layer is responsible for reducing the dimensionality of the input data, creating an output of lower resolution than the input signal, but retaining major features. Pooling layers move over the input signal in exactly the same way as convolutional layers, creating a filter and performing an operation on the image. Unlike a convolutional layer, however, a pooling layer’s filter is prescribed by the developer, not learned. This model utilizes Maximum pooling (also called Max Pooling for short), which retains only the maximum value for each feature map. The final output of a pooling layer is a summarized version of the features detected in the input, making them integral to model’s generalizing power.

Lesion Classification Network

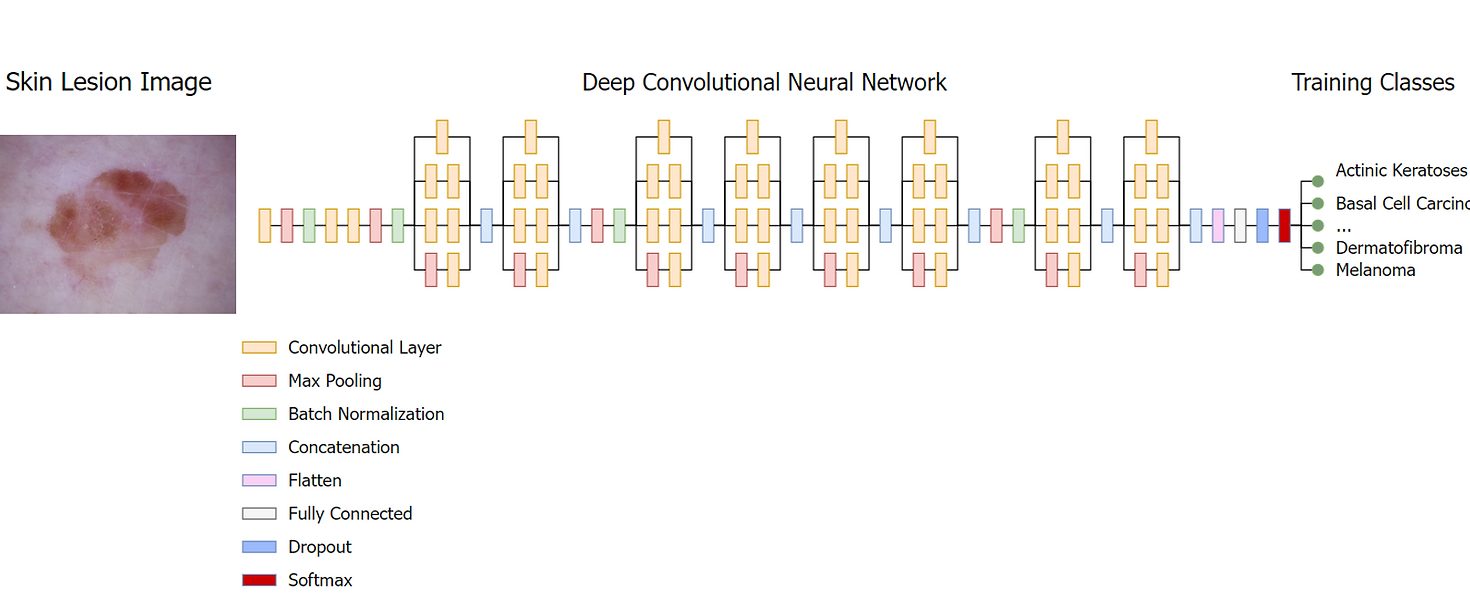

The architecture of the developed CNN, which we will call the lesion classification network (LCNet), accepts images sized to 128x128 with R, G and B channels, followed by a convolutional layer that passes 64 kernels of size 7x7 over the image with a stride value of 2. The primary purpose of this is to develop an immediate sense of features within the spatial domain, utilizing large overlapping kernels to preserve as much surrounding spatial information as possible. The convolution is simple, sliding over the image and transforming the pixel values into a feature map as follows:

\[conv[x,y] = \sum_{i = 1}^k(I_{x -i, y -j} \times F_{i,j}, n_c)\]where \(conv[x,y]\) is the output for the pixel values \([x,y]\) in the spatial domain, \(k\) is the size of the kernel, \(I\) is the size of the input image and \(F\) is the kernel with multiple input channels \(nc\). The resulting feature map is passed to the next layer, a max-pooling layer that transforms map regions by taking their maximum value and reducing their size. As a final step before being passed to the next block, feature maps are passed through batch normalization layers, reducing internal covariant shift through the following process:

\[\begin{align*} \mu_{\beta} &= \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i = 1}^m x_i \\ \sigma_{\beta}^2 &= \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i = 1}^m (x_i - \mu_{\beta})^2 \\ \hat{x_i} &= \frac{x_i - \mu_{\beta}}{\sqrt{\sigma_{\beta}^2 + \epsilon}} \\ \hat{y_1} &= \gamma \times \hat{x_i} + \beta \end{align*}\]where \(\mu_{\beta}\) and \(\sigma_{\beta}^2\) are the input mean and variance, respectively, and \(x_i\) is the new base value for the input \(x\). Batch normalization extends the base formula further by incorporating learned parameters \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\) to produce the final value \(y_i\). Theoretically, this has the effect of transforming an individual neuron’s activation to a Gaussian distribution, i.e., usually inactive, sometimes a bit active, and rarely very active, decreasing training time and vastly increasing precision. Batch normalization has also been show to reduce the effects of exploding and diminishing gradients, reducing the need for further regularization and increasing the learning rate.

Additionally, the LCNet makes extensive use of inception modules, which were popularized with the introduction of the Inception V1 architecture by Szegedy et al. in 2014. Inception modules are particularly effective at reducing computational complexity, making the model wider rather than deeper and thus limiting the effects of overfitting. The most simple implementation performs synchronous convolutions of 1x1, 3x3, and 5x5 kernels over the input signal, passes the resultant feature map to a max pooling layer, and concatenates the outputs to pass to the next layer. The LCNet uses an extended version of this naïve approach, adding an additional 1x1 convolution to limit the number of input channels and significantly improving efficiency. The activation function used is ReLU, a simple, non-linear piecewise function given below.

\[RELU(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } x \leq 0 \\ x & \text{if } x > 0 \end{cases}\]Unlike other activation functions, ReLU is computationally trivial to implement and is representationally sparse, meaning it is capable of outputting a true zero value, leading to decreases in training time and the overall simplification of the model.

This basic structure composes the building blocks of the model, and are repeated in the LCNet to form a deep network capable of extracting information such as edges, colors, textures, and other complex lesion details in the form of a feature map. At the end of the neural network, a flattening layer reduces the dimensionality of the feature map to a one-dimensional array, allowing a one-to-one relation between the cells of feature map and the nodes of the fully connected layer. The model then applies a drop-out layer as a final regularization step. The drop-out layer randomly removes certain nodes from the fully connected layer, limiting the presence of complex and unnecessary adaptations by forcing independent node development. The fully connected layer produces a single feature vector that corresponds to the classification categories and is accepted by a softmax function. The outputs of the fully connected layer are unnormalized log probabilities (also called logits), so a softmax function is applied to transform them into more interpretable normalized linear probabilities.

Notably, skin cancer data as a rule is significantly imbalanced, with heavy skew among several classes of cancer. To address the issue of data under-sampling, the model implemented a class weight system, attaching greater importance to images of underrepresented classes. Moreover, strong data augmentation was applied during network training, including rotations from -320 to +320, scaling with factors of 0.5 in both the X and Y direction, and translation by -2 and +2. These operations were only applied to training sets; test sets were not augmented and their original data distribution was used during the testing process. Generally, deep learning networks suffer from computational cost and limited memory, so the original images are rescaled, ensuring contextual data for the lesions are not lost.

Additional challenges arise from the noise artifacts present in the imagery. To compensate for this, the model implements a simple segmentation algorithm that separates the pigmented lesion from the healthy skin background. This algorithm utilizes a simple mean threshold against the contrasted image to identify the pigmented tissue, adding a light gaussian blur to minimize the interference of any artefacts. By identifying a region of interest, the model is able to operate efficiently and effectively, increasing its generalizing power and limiting computational demand.

The number of learnable parameters in this study is significantly less than many others in the same space, making it less complex and more lightweight. For example, the total learnable parameters used in the study by Iqbal et al. [3] numbered at 256.7M. In contrast, LCNet achieved similarly high performances with only 22M parameters. The network weights are optimized with the Adam algorithm, an extension of stochastic gradient descent that combines the benefits of both AdaGrad and RMSProp. The Adam optimizer is rather simple, calculating the exponential moving average of the gradient and the squared gradient, with the beta parameters controlling the decay of these moving averages. The Adam optimizer has become standard in many deep learning applications given its strong performance. In preliminary testing with the Adam optimizer, the model experienced strong early convergence with the default alpha value of 0.001, but quickly began oscillating. To rectify this, LCNet implements a learning rate decay given by the following:

\[\alpha = \frac{1}{(1 + decayRate \times e_i) \times \alpha_0}\]Where \(ei\) is the epoch number and \(\alpha_0\) is the initial learning rate; 0.001 in this case. This is a commonly implemented method that has proven equally effective in this case, preventing weight updates from overcompensating the model. While this did mitigate some effects of the oscillation, the model experienced better performance when the learning rate decay was combined with a modified epsilon value of 0.01. While the initial epsilon of 1e-8 is optimal for larger weight updates, the fine-grained differences between cancerous skin lesions necessitated smaller weight updates and the resulting trade-off of a slightly longer training time.